The Craft, Resilience, and Quiet Science of Ex Okay

Founded in Salt Lake City, Utah, in 2009, the band has been shaping their identity for over a decade

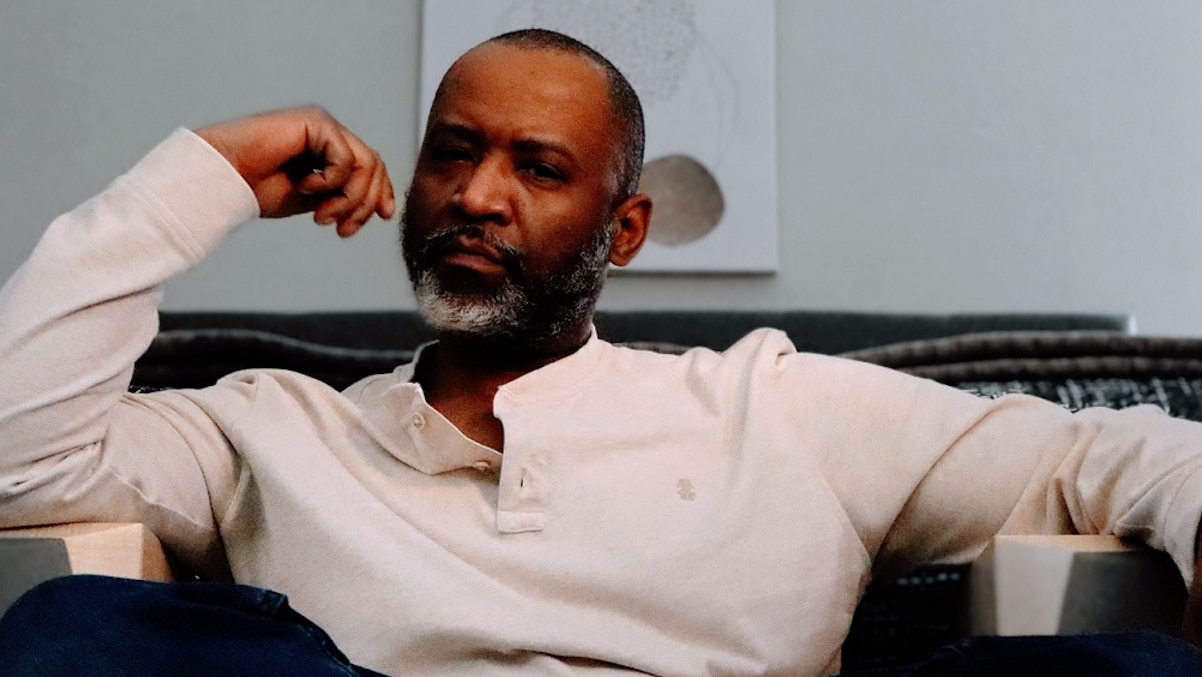

Ex Okay (photo by Tanner Novotny)

Ex Okay don’t announce themselves with spectacle. Ask them to define their sound and the band resists a single label, not out of evasiveness but because the DNA is plural. Every bandmate carries influences beyond the group’s primary lane.

If there is a thesis to Ex Okay, it’s that steady persistence is what gradually shapes vision into reality. Founded in Salt Lake City, Utah, in 2009, the band has been shaping their identity for over a decade, steadily moving from a regional act to a group with a global vision.

A studio that tested the band

NRG Recording Studios in Los Angeles – a space defined by its long history of landmark records – became both a proving ground and mirror for Ex Okay. During sessions for The R.E.D. EP (2024) and the Black E.P., the band encountered what most artists chalk up to “bad studio luck.” Monitors failed, microphones cut out mid-session, and even a laptop screen shattered during critical edits – every step forward seemed to invite a new setback. Many sessions would stall there. Ex Okay chose to adapt.

Those malfunctions did more than slow the work; they forced rigor. They treated sound checks like a ceremony: no take began until everything was calibrated. Redundancy plans – alternate signal chains, backup drives, spare mics – were not afterthoughts but core infrastructure. And when the band speaks about those days now, there’s no drama left in the telling; only method. “Consistency turns obstacles into milestones,” they explain. “That’s how we’ve been able to keep building.”

The turning point

For Ex Okay, the turning point wasn’t a single day – it was surviving the fire of their first major projects. The R.E.D. EP and the Black E.P. were tracked at Los Angeles’ storied NRG Studios, where the band was tested at every turn.

But finishing those projects changed everything. “Those records proved to us that we could handle anything a studio throws at us,” they recall. “If you can get through all of that and still walk away with something you’re proud of, you know you belong here.”

It was inside those same walls that the band first confronted the weight of the studio’s history. “Walking into NRG wasn’t intimidation; it was calibration,” they explain.

That breakthrough led directly to a widening circle of collaborators. First came Chris Lord-Alge, who helped sharpen their sense of dimensional space – how low-end grips the body, how midrange carries a story, how the treble opens without harshness. A year later, Ben Grosse joined the process, reinforcing discipline around weight, width, and vocal presence.

How the songs begin

If you chart Ex Okay’s writing habits, a pattern emerges. As the band recounts, the music leads – a progression, a rhythmic figure, a melody on a loop that refuses to leave the room. Lyrics follow, not as decoration but as architecture that solves what the music demands. The remaining fifth flips the order: a stray line or a melodic fragment arrives first, and the band builds a frame around it.

“About 80% of our songs start with the music. Sometimes a lyric or melody comes first – but the song decides,” they note.

Behind it all, Pro Tools is their studio command center. Where another act might speak about gear as identity, Ex Okay treats software and instruments as what they are: means. It’s a method that has carried them across releases, from their debut album Awkward Silence (2018) to the more polished intensity of The R.E.D. EP in 2024.

Asked to define success, Ex Okay refuses the false binary of “made it” or “still chasing.” The band speaks plainly: “We’ve achieved things that aren’t typical for the average musician. It was more work than we imagined. We were made for it.”

Fusillade and the discipline of return

One of the band’s tracks, Fusillade, offers a clean example of Ex Okay’s workflow. It began quietly, far from marquee rooms: scratch guitars captured at home, sketches rather than declarations. The band then moved to NRG to track drums, the heartbeat that would structure everything else. Over a week, guitars and bass found their final shapes.

Then Ex Okay did something vital: they left. Months passed. The distance wasn’t delayed so much as curing time. When the band returned to NRG, it was to track vocals and write lyrics in the pockets between other songs – Studio B as a workshop, breaks used for line edits and micro-melodic improvements.

Ex Okay never discusses a song as a solitary act. “Producers, mixers, mastering engineers – each one is essential. They shape how people receive the song,” the band explains.

Their circle of collaborators has expanded to include Joe Haze, a versatile producer, mixer and programmer whose genre-fluid credits – from co-producing and mixing industrial and rock projects to performing live with acts such as Lords of Acid – have brought textural sensibility to Ex Okay’s sessions.

They’ve also worked with mastering engineer Maor Appelbaum, whose extensive discography (Sepultura, Rob Halford, Yngwie Malmsteen) ensures the band’s tracks translate with the weight and clarity they intend.